Looted Iraqi Antiquities Return Home After UK Experts Crack Cold Case

9 August 2018

British Museum traces exact origin of treasures, brought to London after Saddam Hussein’s fall.

A collection of 5,000-year-old antiquities looted from a site in Iraq in 2003 after the fall of Saddam Hussein, and then seized by the Metropolitan police from a dealer in London, will be returned to Baghdad this week.

It comes after experts at the British Museum identified not just the site they came from but the temple wall they were stolen from.

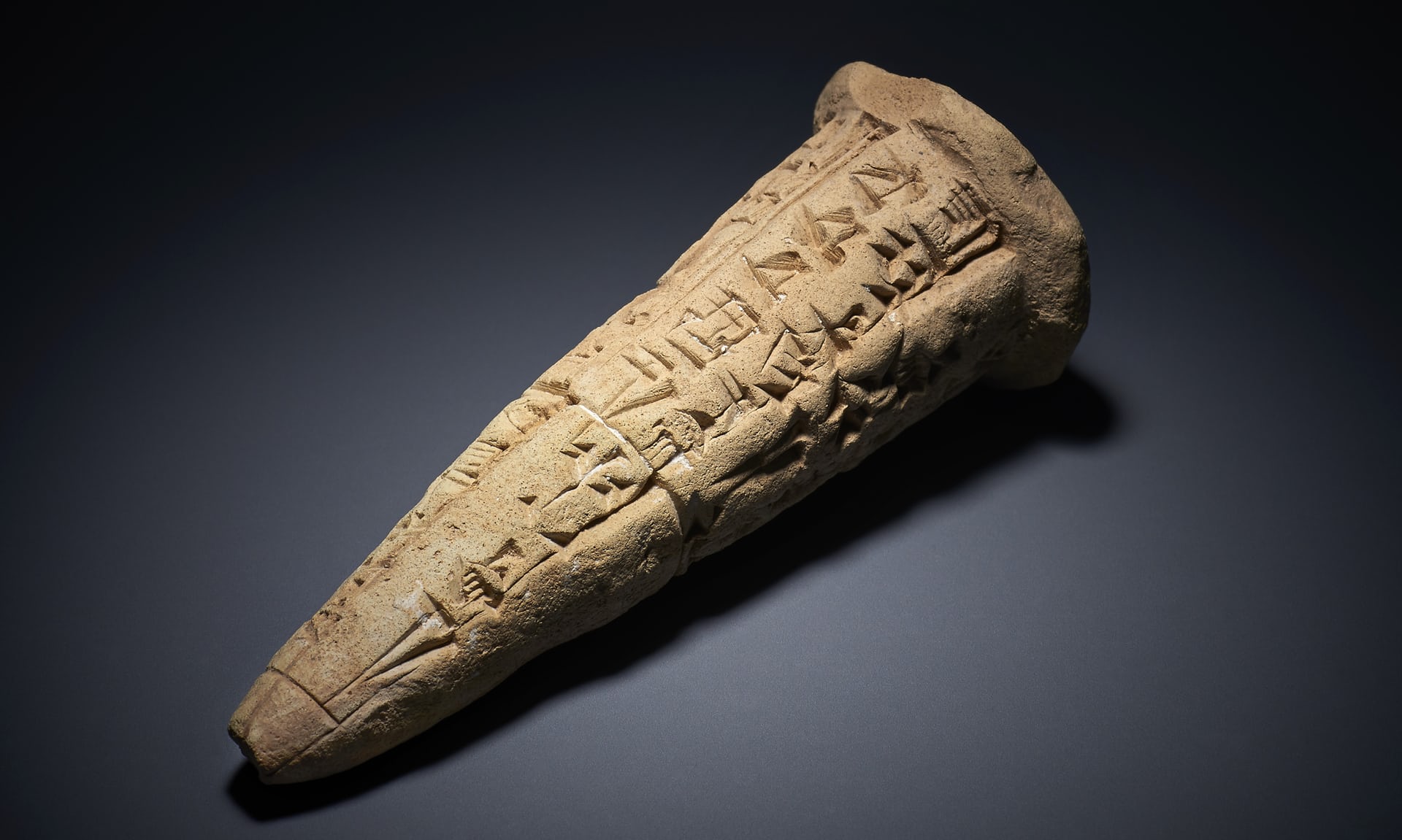

The eight small pieces had no documentation of any kind to help the police, but the museum experts could literally read their origin. They included cone-shaped ceramics with cuneiform inscriptions identifying the site as Tello, ancient Girsu in southern Iraq, one of the oldest cities on earth recorded in the earliest form of true written language.

The inscriptions named the Sumerian king who had them made almost 5,000 years ago, the god they were dedicated to, and the temple. And by an extraordinary coincidence the museum had an archaeologist, Sebastian Rey, leading a team of Iraqi archaeologists at the site, uncovering the holes in the mudbrick walls of the temple they were torn from, and the broken pieces the looters had discarded.

On Friday the museum will present all the pieces, including carved seal stones and a tiny marble amulet of a bull, packed into a handsome red velvet case recycled from the museum stores, to the Iraqi ambassador Salih Husain Ali.

He said the protection of antiquities was an international responsibility and praised the British Museum and its staff “for their exceptional efforts in the process of identifying and returning looted antiquities to Iraq. Such collaboration between Iraq and the United Kingdom is vital for the preservation of Iraqi heritage”.

St John Simpson, the assistant keeper at the Middle East department of the museum, said: “Uniquely we could trace them not just to the site but to within inches of where they were stolen from. This is a very happy outcome, nothing like this has happened for a very, very long time if ever.”

They will be returned to the national museum in Baghdad and reunited with many objects from the recent excavations, and may eventually be loaned to a museum near the site.

The site of the Eninnu temple at Tello is now protected, not just by the reformed Iraqi archaeological police, but by a local tribe. It was excavated by French teams from the late 19th century into the 1920s, and the distinctive inscribed cones, imitations of tent pegs in fired clay, were noted from the 1870s.

The site was never forgotten locally. Rey says pieces of pottery and inscriptions still turn up scattered across the surface of the tells, the mounds covering the ruins. In the chaos after the fall of Saddam Hussein, there was widespread looting of Iraqi sites, some on an industrial scale. But the museum experts believe the raid on Tello was more opportunistic, probably by one individual over one night. Simpson described the collection as “a pocketful of little treasures”.

The pieces are believed to have come to London within months or even weeks of the fall of Hussein. The Metropolitan police seized them from a dealer who had no documentation for them, made no attempt to reclaim them, and has since gone out of business.

With no apparent way of tracing their origin, they sat in police stores until some of the antiquities cold cases were reopened with the reforming of the Met’s art and antiquities squad, and brought to the museum earlier this year. The British Museum has been training Iraqi archaeologists and conservators for several years and then working with them in the field.

The team at Tello is finding broken cones identical to those recovered in London. Imitating tent pegs, they were originally placed into holes in the mudbrick walls of the temple to invoke and capture the powers of the Sumerian Thunderbird, a lion-headed god whose body flashed lightning and whose roar thundered.

However, Rey’s favourite piece is the most modest: an oval polished river pebble with an even older inscription in the most archaic form of Sumerian script. It begins with a star, which indicates that the name of a god follows, and is a dedication to the god of water and floods, “very appropriate to a pebble from the river,” Rey said. The slightly wobbly inscription is broken off, as if more than 3,000 years ago the workman was disturbed at his task.

Rey and Simpson said it was not just a bit of classic detective work to resolve an archaeological cold case. The illicit trade in antiquities relies on the difficulty of tracing the origins of small pieces and the date they left their countries – many, sold with no provenance, and the vaguest of sites, are claimed to come from old collections.

The museum experts hope their methodology could be used to create maps of specific sites and types of antiquities, making the work of looters much more difficult.