The Salary Crisis of Teachers and Employees in the Kurdistan Region: 11 Years of Waiting and Protesting

Shamal Raof, Kurdistan Social Forum

The Kurdistan Region is a part of the federal state of Iraq under the constitution ratified after 2003. Until 2014, the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) received its share of the federal budget from Baghdad. However, that year witnessed an escalation in political and economic disputes, particularly after the KRG began selling oil independently without coordination with the central government and declared economic autonomy. As a result, Baghdad decided to halt the region’s budget payments.

Since then, teachers and public employees in the Kurdistan Region have suffered from a chronic salary crisis. As of 2025, the salaries for May and June have still not been paid. The crisis affects all public employees in the region and is a direct consequence of political wrangling where citizens, not politicians, pay the price.

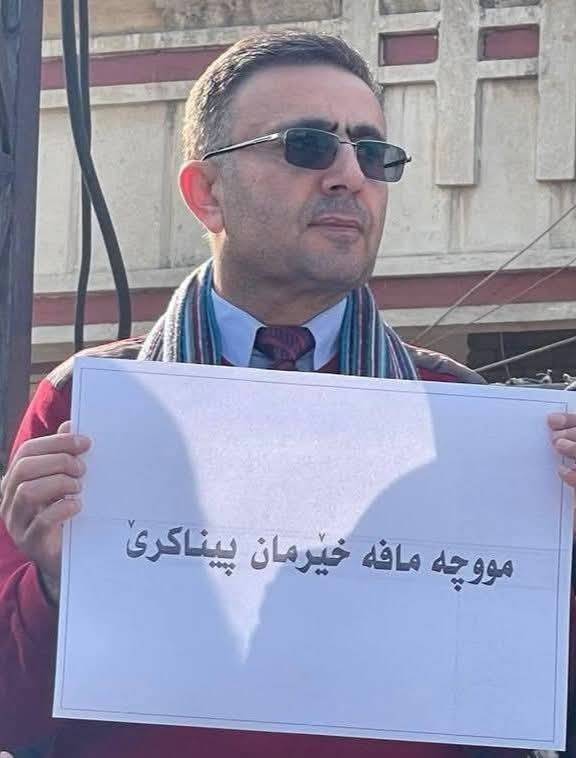

Mohammed Sharif, a teacher and civil activist involved in the teacher protests, explains:

“Until 2014, the Iraqi government sent 1.3 trillion Iraqi dinars monthly as the region’s share. But after the KRG declared economic autonomy, the budget was halted, and the salary crisis began.”

He continues with the breakdown of the salary situation:

“Out of 121 months, only 58 full salaries were paid. Eighteen months went unpaid entirely. In 34 months, only a quarter of the salaries were paid. In 9 months, salaries were cut by 21%, and one month saw an 18% cut. Additionally, job promotions were frozen to avoid salary increases.”

Sharif adds: “Recently, Baghdad agreed to send salaries to KRG employees, but on the condition that the oil file, border crossings, and internal revenues are handed over to the central government and that salaries are disbursed through banks. However, the ruling parties in the region oppose this, fearing it would end their control over oil trade and revenue collection.”

He concludes: “The leaders of the region live like royalty and are fully capable of paying salaries from their resources. But they don’t care about the people’s suffering. They are more invested in regional power struggles that serve their interests.”

Women on the Frontlines: Protests, Imprisonment, and Threats

Shna Ali Khayat, a teacher from Sulaymaniyah, is one of the leading female figures in the teacher protests. She has been protesting since 2014 and has been arrested twice.

She says: “During the last protest in Sulaymaniyah in July 2025, I was arrested. Before that, I participated in continuous strikes, including setting up tents outside the courthouse for two weeks, a hunger strike in front of the UN office for 15 days, and blocking the Arabat road used to export oil.”

Regarding threats, she adds: “Once, armed men tried to kidnap me in front of my house, but I managed to escape.”

Despite the violence, Shna says: “Security forces treated us violently on the streets, but the treatment inside detention centers was relatively better.”

Proud of her role in a society lacking female leadership, she says:

“I’m proud to be a symbol of hope. I’ve never feared being judged as a woman. On the contrary, it strengthened my commitment to civil struggle and made me a source of inspiration for men.”

What saddens her most is “the silence of the people, the lack of response to protests, the division, and the absence of trust between the public and protest groups.”

Erbil: Between Silence and Fear

In Erbil, the capital of the Kurdistan Region, protests are rare. Some attribute this to fear of the authorities, while others believe people have lost faith in change.

Mohammed Joumani, a teacher, civil activist, and writer who led protests in Erbil until 2018, shares:

“Since 2014, there were small-scale marches and protests. In 2015, they expanded. In 2016 and 2017, we demonstrated several times in front of the regional parliament. Once, we stormed the Ministry of Education, interrupted a cabinet meeting, and forced the minister to listen to our demands.”

He continues: “On March 24, 2018, we held our first meeting to establish a council to cancel salary delays in Shanadar Park with 20 teachers. The next day, thousands protested, and dozens were arrested or tortured.”

“Protests then spread to Duhok and Soran. Under public pressure, the government raised salaries from 25% to 80%. But soon after, protests were silenced through arrests and intimidation.”

On the current absence of protests, Mohammed explains:

“In Erbil, no protest is tolerated. People are afraid. In Sulaymaniyah too, if the ruling party disapproves, protests are suppressed, and participants are jailed.”

These testimonies expose the depth of the crisis: a political and economic conflict for which ordinary citizens pay the price. Salaries—meant to be guaranteed rights—have been turned into tools of political blackmail, under a system of mutual complicity between regional and central authorities that lacks transparency and accountability.