Do the Iraqi Youth Protests of 1 October Represent a Nonviolent Movement?

The Iraqi Civil Society Solidarity Initiative – 18 October 2019

The uprising of 1 October, which was launched from Tahrir Square in Baghdad, called for peaceful demonstrations. But in the days that followed, there were an enormous number of victims, as many as 108 dead and about 7,000 injured (according to official sources). These victims were mostly protesters, but also included some police and security forces. The protests also saw violence of another kind, such as the burning of the headquarters of political parties, in particular in the province of Dhi Qar, and the burning of police and army vehicles. There were also attacks on offices of TV channels that had covered the Baghdad protests. Where did the violence come from?

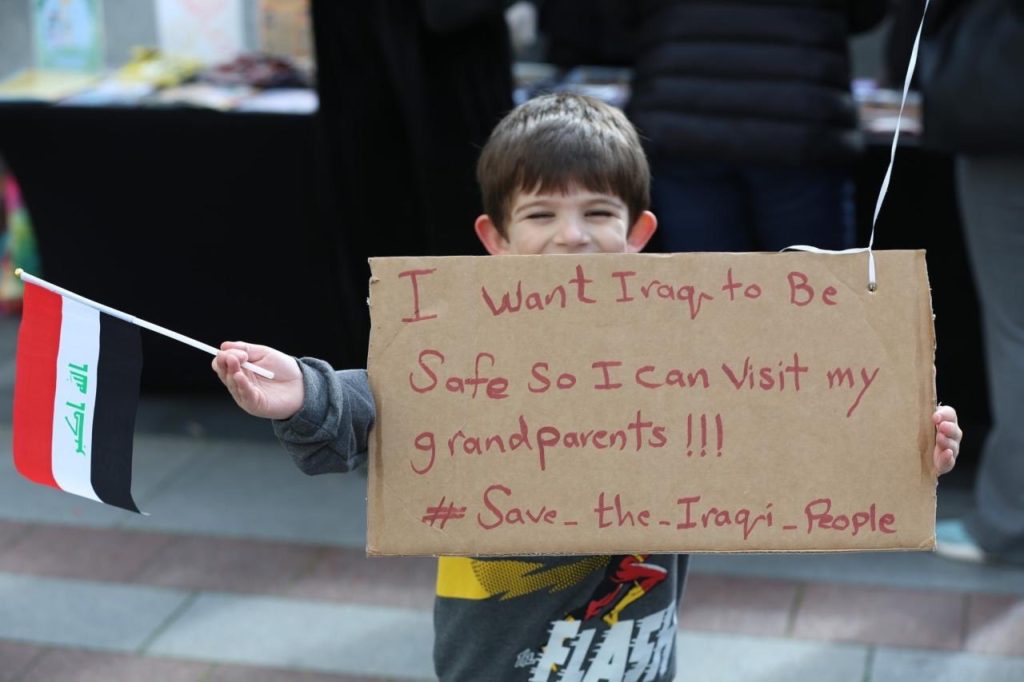

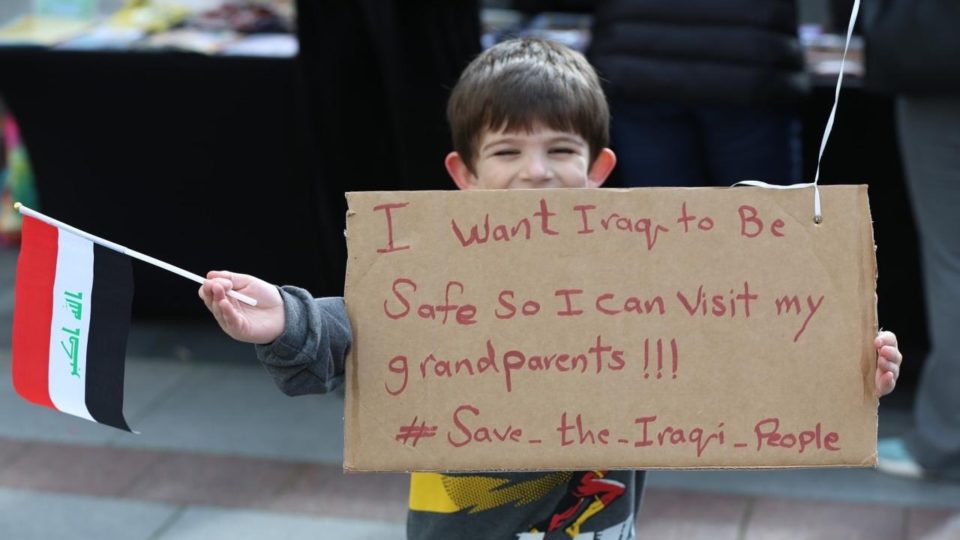

Let’s begin with the core protests in the main public squares in Baghdad. All indications are that the protests began peacefully. Videos and pictures show protesters holding flags and mobile phones, shouting “Peaceful, peaceful”. Some of them carried banners saying:

“We protest peacefully; don’t shoot us”, and “Don’t kill us”.

This was the case in Baghdad, Dhi Qar, and Diwaniyah, and also in the provinces that joined the protests after 1 October.

A large number of demonstrators also specifically rejected the acts of sabotage that accompanied the protests. They expressed this on more than one occasion, symbolized by a photograph of a young activist involved in the protest movement in Basra who carried a banner

“I’m a protester, I’m against sabotage.”

These demonstrators explicitly rejected all acts of destruction of state property. But this did not prevent retaliation against the activist Hussein Adel, who was assassinated in his home along with his wife, Sarah, also an activist with the protest movement in Basra.

Repression of the protests

In Baghdad, confrontations and repression began when riot police tried to disperse demonstrators from Tahrir Square and prevent them from moving to the Jumhoriya Bridge by firing tear gas, hot water, and live bullets. This was confirmed in a report of the Peace and Freedom Organisation and Al-Namaa Center for Human Rights titled, “Whips of Repression.”* One of the demonstrators wrote on her Facebook page that the police continued their pursuit through the streets and alleys near Tahrir Square. Vehicles ran over a number of protesters; others fell after they were directly fired upon, and all this led to many victims and martyrs among the protesters. The next day, the protests continued and the number of protesters increased, all the while spreading to other provinces. Over the following days, security forces from the SWAT (Rapid Deployment Forces) and anti-riot forces surrounded the protesters in a number of the alleys adjacent to the squares where protesters were demonstrating. Security forces raided stores and restaurants that were assisting the protesters. Some protesters erected barricades and threw stones or burned tires. Pictures were spread via social media showing scenes of young protesters getting shot by live bullets while talking to the camera. The government used similar methods of repression in other provinces.

The government also imposed a curfew, blocked social media sites and even shut down the internet entirely, allowing only limited service at particular hours with a very weak signal. All this is widely regarded as a government tactic to prevent the dissemination of any those materials that might aid the demonstrations, and to prevent protesters from organizing and mobilizing on social media.

As events continued and escalated, other groups joined in carrying out the repression. Iraqis are familiar with the anti-riot forces, the SWAT forces, and the police. However they do not know who is responsible for the deployment of snipers in Baghdad and other cities. These snipers shot directly at protesters with a clear intention to kill. Indeed, protesters spread footage of a number of people being shot in the head or neck. The report, “Whips of Repression”, confirmed many such killings. Activists spread photos and videos on social media, some of which were deleted because they depicted “inappropriately bloody” scenes.

The Iraqi public suspects that these snipers probably belong to or are allied with the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) (al-Ḥashd ash-Shaʿbi) or other related factions, although this remains uncertain. The PMF is officially considered part of the Iraqi armed forces and is therefore under the command of Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi; however, it is difficult to say exactly who gave orders to the snipers or whom they were obeying. The Iraqi Interior Ministry claimed that the Iraqi government does not know who the snipers are or who deployed them. The government nonetheless bears responsibility for the crimes committed by the snipers, especially since they often used governmental buildings to shoot from.

Unidentified armed groups also stormed the offices of TV stations, particularly in Baghdad, destroying equipment and assaulting staff in order to halt broadcast of the protests. It was a group like this that stormed the apartment of the activist Hussein Adel and his wife Sarah and shot them both to death. Other activists have been abducted by unidentified armed groups.

Although it is difficult to accuse any specific group, it is clear that these armed individuals were working intentionally to suppress the protests. The Iraqi public suspects that they are connected to influential political parties in the current government and the existing Iraqi political system. In summary, it appears that the system of repression of the October protests involved more than one actor and probably included the following:

1) Anti-riot forces – Governmental

2) SWAT forces – Governmental

3) Army forces – Governmental (announced later to have withdrawn from Sadr City)4) Organized sniper teams – suspected of being linked to the security of the Popular Mobilization Forces, though this is yet to be confirmed

5) Armed groups and security guards from the headquarters of influential political parties – especially in the provinces of southern Iraq: Dhi Qar, Amara, and Diwaniya

A nonviolent movement requires more than calling for peaceful protest

It appears from media reports and other information circulated after the demonstrations that most of the protesters were peaceful. Some did nonetheless resort to throwing stones and burning tires with the intention of blocking the roads. These are common tactics of protesters in many places. Even if the majority of protesters remained nonviolent, there is also no denying the existence of some who tried to promote violence, likely because of frustration that peaceful methods were not bringing about change quickly enough. Additionally, when the Ashira (members of extended family clans) from the Southern Governorates and from Sadr City (Southern Baghdad) joined the protests following the funerals of their sons who had been martyred, the headquarters of political parties, especially in Nasiriyah and Dhi Qar, were set on fire in what seemed to be acts of revenge. And in Baghdad some protesters destroyed military vehicles.

These protesters were not committed to a sustainable, nonviolent struggle, which must include strategic planning, unified leadership, and genuine openness to negotiating the demands of all parties involved. While Iraqis celebrate the fact that the protests of 1 October were spontaneous and had no unified leadership—because they consider this to be proof of their independence—at the same time this “independence” likely contributed to the movement’s failure to reach its desired results. Slogans and signs calling for the overthrow of the government complicated the dynamics of the movement and may be one of the reasons for the escalation of repression. It is difficult to negotiate a radical demand like “overthrow of the government” even when there is little or no confidence that the government will keep its promises. Still, the Iraqi government and the ruling political class must be held accountable; this is is a critical goal of the current protest movement.

Protesters are now gearing up to launch a new movement, and plan to start it on Friday 25 October, following the religious observance of Arba’een. Demonstrators are rallying on social media and circulating their demands. Some of these demands are quite radical, for example, one social media post from Southern Iraq requests the following:

1) Repeal the constitution;

2) Change the Iraqi governmental from a parliamentary to a presidential system and elect the president directly;

3) Abolish all political parties.

It is not clear whether there is a unified leadership, whether someone is directing the movement with a plan to negotiate these demands in a practical and effective way. A nonviolent protest movement capable of reforming the existing political system will require a profoundly peaceful and disciplined leadership, one which has a true grasp of the principles and methods of nonviolence.