Who is Responsible for Destruction of Iraq’s Cultural Heritage?

BAGHDAD, Iraq — Safeguarding Endangered Cultural Heritage, a conference held in Abu Dhabi December 3-4, called for international support to protect the endangered cultural heritage of the Middle East, especially in Iraq and Syria. Conference participants approved establishing a $100 million fund and a safe haven network for use during conflicts. The problem in Iraq is one of conflict as well as neglect.

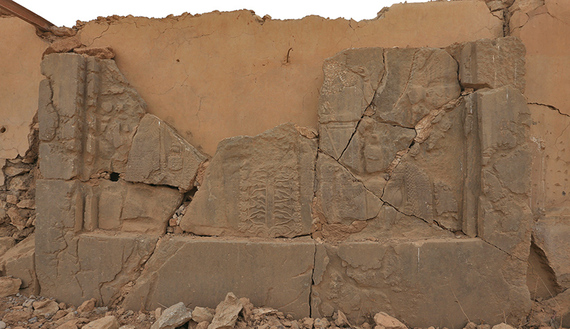

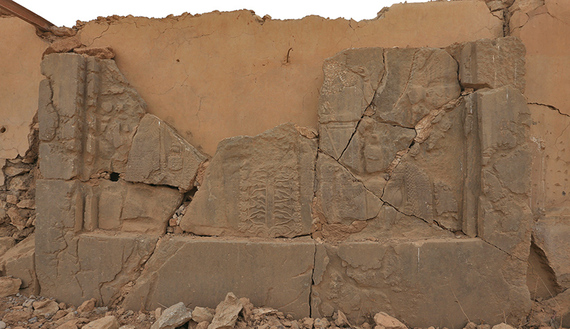

On Nov. 25, after the liberation of Nimrud — the Assyrian archaeological site south of Mosul — from the Islamic State (IS), UNESCO Director-General Irina Bokova announced, “The damage inflicted to Nimrud is a major loss for Iraq and for the world.” She also asserted, “The protection and rehabilitation of Iraqi’s heritage, in Nimrud and beyond, is essential for stability and cohesion in the country and the entire region.”

The destruction of Iraq’s cultural heritage is not limited to extremist groups like IS and widely known ancient sites. Some governorates and municipalities are also culpable in the neglect and destruction of locally historic places. For example, on Nov. 13, the local government in Diyala gave a developer permission to demolish the oldest cinema in the governorate, a cultural and entertaining landmark built in 1949. Its decision raised the ire of a broad segment of the population, which viewed the act as “uncivilized” and a sign of “ignorance” about the importance of culture and heritage.

Ali Abu Iraq, a freelance writer and heritage activist, told Al-Monitor, “Demolishing cinemas in places in Iraq is attributable to radical thinking and ideologies, wherein the art of cinema is forbidden and conflicts with Islamic values.” Abu Iraq also sees the demolition of historic buildings and other landmarks within the context of a struggle between heritage and investment.

Some owners of historic houses seek financial gain by converting their properties into commercial businesses, contrary to the Law of Antiquities and Heritage.

On Aug. 5, the Secretariat of Baghdad approved the demolition of the former home of Sassoon Eskell, who was instrumental in establishing the government and financial system of post-Ottoman Iraq and became its first finance minister. The authority said the house was not a listed site and could therefore be demolished to make way for a commercial development.

The secretariat had claimed in December 2015 that it would take “strict measures to prevent the conversion of heritage homes to commercial buildings” and therefore would not be granting permits in such situations.

The reality, however, is completely different. On May 18, 2016, the Music Studies Building, established in the 1930s in Baghdad, was demolished for commercial development.

Some landmark buildings have fallen under the control of political parties, some of which simply took over the property. Mowaffak al-Rubaie from the State of Law Coalition took control of a house on Haifa Street in Baghdad following the 2003 US-led invasion. When he made it his party’s headquarters, it sparked protests on March 10 and demands that he vacate the property.

In Kirkuk, protests broke out Nov. 11 against a project to convert a section of Kirkuk’s historic citadel and its market — said to be about 100 years old — into a shopping mall.

In Karbala, a Safavid era section of wall of the Khan al-Atishi, an ancient inn, crumbled to the ground Aug. 16, putting the rest of the monument in danger of collapse. Similarly, the Sharabiya School in Wasit, built in 1234, collapsed over time, leaving only the main gate standing.

Earlier this year, a hotel project in the city of Najaf led to the destruction of part of the historic city wall, which dates to 1217. The University of Kufa annexed the King Faisal II Palace, built in 1946, and now uses it as an educational facility. In March, Al-Monitor examined another form of heritage destruction in Najaf, reporting on people looting old Christian graves in search of valuable relics, collectibles and gold.

Jabbar Kawas, head of the Union of Writers and Poets in Babil, who is also versed in heritage issues in the area, told Al-Monitor, “The owners of heritage homes have offered them for sale as they are now in the heart of commercial centers.” He added, “Most of the heritage houses throughout Babil are dilapidated, without effort being made to restore them.” Kawas blamed the situation on poor cultural awareness and therefore lack of knowledge about the importance of such monuments, stressing that the solution to saving remaining heritage houses is to have laws to protect them and to develop plans for restoring them.

Shwan Dawoodi, a member of the Culture and Information Committee in the Iraqi parliament, told Al-Monitor, “Those who are destroying these places are in my eyes akin to the Islamic State, which demolished archaeological sites in Nineveh.”

Dawoodi does not deny the government’s own neglect of heritage monuments and cultural venues, but lamented, “The parliament’s Culture and Information Committee condemns such acts but remains powerless to prevent them.” Dawoodi called for strict measures to deter conversions of heritage houses into commercial properties and stressed the need to allocate sufficient funds for the reconstruction and restoration of neglected archaeological sites.

There are close to 1,800 heritage houses across Iraq that have been registered with the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. The development of a working plan is sorely needed to start the work of protecting and restoring them. Turning some of these buildings into tourist attractions could be profitable for their owners and thus incentive not to convert them into commercial properties.